I have spoken to countless folks over the years who want to do a redesign of their website. During these conversations, I typically hear something like:

- “Our website has gotten out of hand”

- “The pages on our site look so different from one another”

- “There is zero organization at all.”

- “I don’t even know where to begin.”

If this is you, know this problem is assuredly solvable.

This mess happens mainly because of a few reasons:

Too many cooks in the kitchen

There is more than one person working on the website’s content. Different people have different “eyes for design” and therefore pages created by each person look a little bit different. The root cause of this is that a website’s building blocks are too flexible (and allow editors to change every little color and font size), but that’s a post for another day.

Building quick, one-off pages

We’ve all done this before: we have a marketing campaign and just need a quick page spun up under a short URL. What isn’t considered is how to organize that page so you know you can delete it six months later. Every page created ends up being saved at its most convenient location; therefore, there isn’t a simple way to find and remove these dated pages.

Why does it matter?

If you are reading this and your site only gets updated a few times a year, this probably won’t matter to you (however, you should consider what it would look like to use your site on a regular basis). For the rest of us who do, there are a few reasons why a solid plan will help in the long run. Also, there are a few times I’ll need an example. I’ve jotted down a sample sitemap below:

| Page | URL |

|---|---|

| Services | domain.com/services |

| Services > Plumbing | domain.com/services/plumbing |

| Services > Plumbing > Toilets | domain.com/services/plumbing/toilets |

| Services > Plumbing > Sinks | domain.com/services/plumbing/sinks |

| Services > Plumbing > Outdoor | domain.com/services/plumbing/outdoor |

| Services > Electrical | domain.com/services/electrical |

| Services > Electrical > Wall Outlets | domain.com/services/electrical/wall-outlets |

| Services > Electrical > Breaker Box | domain.com/services/electrical/breaker-box |

| Services > Electrical > GFCI | domain.com/services/electrical/gfci |

Ease of deletion

We’ve already talked about it, but it allows you to clean your site much simpler. You can go to a page, view all of it’s subpages, and easily clean house when you need to.

URLs that collapse

While this gets technical, you want your URL structure to make sense. Let’s look at the page structure above. I’m actively on the Wall Outlets page. I want to get back to the main Electrical page, but there isn’t a link on the page to do so. I could go to the URL in the address bar, remove the word “electrical” and I would be sent to the main Electrical page.

In short: all of the segments of your URLs make sense. If a user were to go and delete pieces of the URL, you want them to be able to get to where they think they will go.

Automated content

This is especially true for websites that contain hundreds of pages. When a website is organized with pages and sub-pages thought out, it allows for a lot of dynamic content that your marketing team does not have to manually populate.

Using the example above, the main Plumbing page could dynamically show a list of the three pages that are underneath it (Toilets, Sinks, and Outdoor). If a new page was added under Plumbing, the main Plumbing page would automagically be updated when that page is published.

An intentional structure saves time.

Customer-based thinking

When working on page structure, the core thought should be: what problem does your customer need to solve? A potential customer could go down a few different paths. Those paths should be the starting point for how a website’s content is organized.

If we’re looking at an industry that is highly transactional – and clients know exactly what they want – then a page outline much like the above would do just fine. (the company’s personality and story need to be injected a lot throughout the way).

In a business that is a bit more relationship-driven, thinking through how a customer processes the problem they are having is paramount. If the words on the page can get them to think:

- “Oh yeah, that does sound like me!” and

- “I hadn’t thought about it like that before …”

Then you are already moving them in the right direction. The pages of your website should follow that person’s thought process, and allow them to dive deeper in the areas they are interested in.

Let’s get started

Simplify. Simplify. Simplify.

If you don’t hear anything else from this article, start simple and stay simple.

I want to first pose a challenge to you:

You only have seven pages to get your points across. All seven pages will be in your main navigation. What are those pages?

List your main seven pages

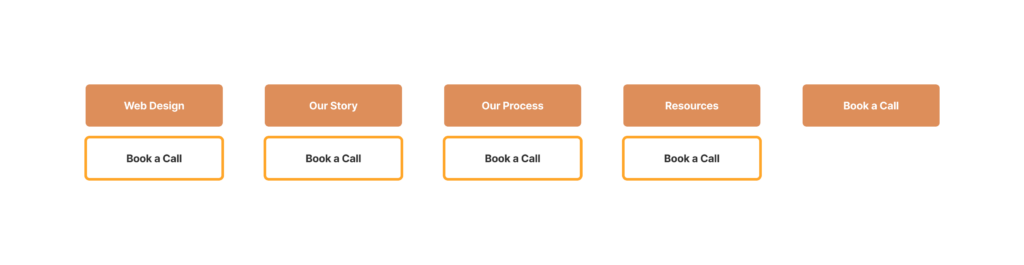

Go ahead and write them out. And make sure to leave some space under each one. I went ahead and did mine:

Define each page’s action

Now that we have the list of pages that are key, let’s answer: what is the main action (CTA – or call to action) I want people to take when visiting this page? Knowing the one thing you want any visitor to do when visiting each page will help you craft the page’s content.

For me, the primary CTA across all these main pages would be to schedule a call. If you are in the services business, I highly recommend having a scheduler as your primary CTA across your site.

What topics should be discussed on each page?

From here, I want you to now start thinking of what questions a visitor may have when they visit each page. To get your thought process started, here are some questions to consider when thinking about each page. When a user visits this page:

- What questions would they have?

- What are they looking to solve?

- What action are they potentially ready to take?

- What did they see on my competitor’s websites?

Now that you have all of the topics listed, go through each and ask:

Can I answer this question in a paragraph, or does it deserve it’s own page?

Chances are, you’ll find that you can answer most questions in a single paragraph. I recommend starting there. If you find out that you are answering the same questions from your clients again and again, use that as a push to create subpages that have more in-depth explanations.

You’ll also see some lines being drawn to connect similar sections. In my example above, I have Samples under the Web Design page, but I also have Case Studies under Resources. Those are the exactly same.

The next question I would ask myself is: “where does it make sense for Case Studies to be stored permanently?” The answer: they are Resources, and therefore should be saved there.

When I’m building my page for Web Design, I would reference Case Studies under Resources.

But what about all my other content?

If you run a website that has hundreds of pages of content, a sitemap that is a bit more robust will assuredly be needed. However, starting simple is never a bad idea.

From here, I recommend going through the other pages that would need to be migrated and do two things:

- Bucket them together in similar categories

- Pick which main page each bucket should go under

It is a bit more nuanced than that for larger websites, but that is at least a solid starting point.

What’s next?

Go off and make your website simpler! I dare you to start with pencil and paper – forcing yourself to actually write it out will help keep everything simpler.

I’d love to chat. If dealing with your sitemap and calls to action is overwhelming, I’d love to help you out. Drop a time on my calendar and we can go over it. Together.